For thousands of years, humans across cultures have fermented fruits, grains, and honey to create alcoholic drinks. From ancient rituals to modern happy hours, alcohol has played a persistent role in social life. While today it is often associated with relaxation or celebration, the reason alcohol feels good goes much deeper than taste or habit. Evolutionary biology, brain chemistry, and early human survival strategies all help explain why our brains respond so positively to alcohol.

Understanding this connection reveals not only why alcohol can feel rewarding, but also why moderation has always been important.

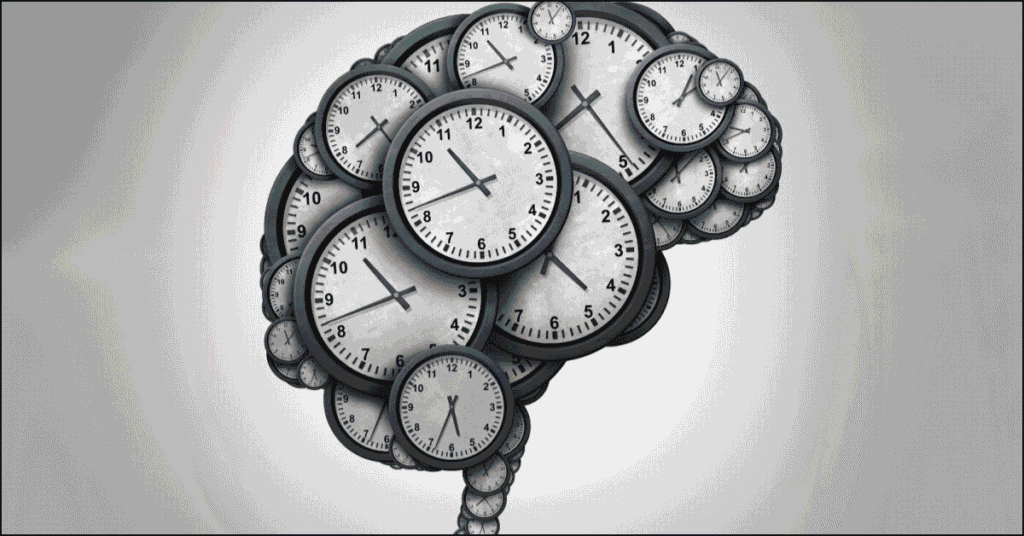

Alcohol and the Human Brain: A Chemical Shortcut to Pleasure

At its core, alcohol affects the brain’s reward system. When consumed, alcohol increases the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter linked to pleasure, motivation, and learning. Dopamine is also released when we eat calorie-rich foods, bond socially, or achieve goals—activities that historically supported survival.

Alcohol also boosts endorphins, the body’s natural “feel-good” chemicals that reduce pain and increase relaxation. Together, these effects can produce feelings of warmth, confidence, and reduced stress, especially in social situations.

From a biological standpoint, alcohol temporarily mimics signals associated with safety, abundance, and social bonding—conditions our ancestors strongly favored.

The Evolutionary Link to Fermented Fruit

One leading evolutionary theory is known as the “Drunken Monkey Hypothesis.” It suggests that early primates who could detect and tolerate naturally fermented fruit had a survival advantage.

Fermented fruit:

- Was often riper and more calorie-dense

- Emitted ethanol aromas that helped locate food from a distance

- Provided quick energy in the form of sugars

Primates that evolved a preference for low levels of ethanol were more likely to find these valuable food sources. Over time, humans inherited this biological sensitivity to alcohol’s smell and effects.

In short, alcohol wasn’t originally a recreational substance—it was a signal of nutrition.

Alcohol as a Social Bonding Tool

Human survival has always depended heavily on cooperation. Alcohol reduces activity in the brain’s prefrontal cortex, the region responsible for self-control, caution, and social anxiety. This reduction can make people feel more open, talkative, and emotionally connected.

In early human groups, shared intoxication may have:

- Strengthened group bonds

- Reduced conflict during communal gatherings

- Encouraged storytelling, rituals, and cooperation

Even today, alcohol is commonly used in social settings where trust and bonding are important, such as celebrations, ceremonies, or informal gatherings.

Stress Reduction and the “Safe Signal” Effect

Alcohol also enhances the effects of GABA, a neurotransmitter that slows brain activity and promotes calmness. This creates a temporary sense of safety and relaxation.

From an evolutionary perspective, anything that reduces stress signals in the brain can feel rewarding—especially in environments where threats were common. Alcohol essentially tells the nervous system, “You are safe right now.”

However, this is a temporary chemical signal, not a solution to stress itself.

Why the Good Feeling Doesn’t Last

While alcohol can feel pleasurable in the short term, the brain quickly tries to restore balance. As dopamine and endorphin levels drop, the brain may produce:

- Fatigue

- Low mood

- Anxiety or irritability

This rebound effect explains why excessive or frequent drinking can lead to diminished enjoyment over time. The same evolutionary system that once helped us survive can become overstimulated in modern environments where alcohol is easily available.

Evolution Didn’t Plan for Modern Drinking Habits

Our ancestors encountered alcohol in small, natural amounts through fermented fruit or early brews. They did not have access to distilled spirits, high-alcohol beverages, or daily consumption.

Evolution shaped our brains for scarcity, not abundance. Modern alcohol availability can overwhelm systems that were designed for occasional exposure, not constant stimulation.

A Biological Preference, Not a Biological Need

Alcohol feels good because it taps into ancient reward pathways meant to reinforce survival behaviors like eating, bonding, and resting. But those pathways were never intended to be activated frequently or in isolation.

Understanding the evolutionary science behind alcohol can help explain:

- Why it feels pleasurable

- Why it encourages social behavior

- Why moderation matters

Final Thoughts

Alcohol’s appeal is not accidental—it is rooted in millions of years of evolution, brain chemistry, and survival instincts. What once helped humans locate food and bond socially now plays a very different role in modern life.

Recognizing that alcohol’s “good feeling” is a biological shortcut—not a necessity—can encourage more mindful choices. Evolution explains why alcohol feels good, but awareness helps us decide how to use it responsibly.